An afternoon in Ticuantepe

The rocking chair in the corner of the front verandah was the best place to sit while the twins took their early afternoon nap. It was when the mountain breeze would pick up, gentle at first, heavy with the scent of leaves and bark from the damp forest floor. It felt delicious on my sweaty skin. Soon it would blow away the wisps of smoke that lingered from the smouldering piles of rubbish on adjoining properties. The traffic drummed in the distance. A hummingbird zipped across the bright hibiscus flowers, and orioles chased insects. On lucky days, a curious guardabarranco would perch on the fence and utter its raucous trill.

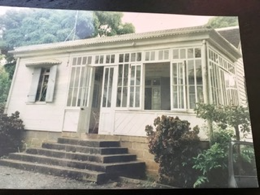

The second Ticuantepe house

The still active Volcan Masaya occasionally rumbled as it ‘degassed’, but the inhabitants of surrounding towns and villages still went about their business, oblivious to the impending threat of an eruption. They seemed immune to tragedy, having survived devastating earthquakes and decades of despotism pre- and post the contra wars. With deep religious fervour, Nicaraguans have placed all responsibility for their fate squarely in the lap of God. Si Dios quiere, they will be safe.

Rocking gently, I open the little book gifted to me by my grand-daughters last Christmas. Para mi abuela (‘For my grandmother’) is a book of quotations that celebrate the love shared by grandmothers and grandchildren. I open it randomly, allowing my thoughts to roam on the first words that appear:

Mi abuela siempre me dicía que el día estaba perdido si non habías reído a carcajadas por lo menos una vez. (‘My grandmother always told me that the day was lost if you had not laughed aloud at least once.’)

I unfortunately never knew a grandmother who could have taught me to laugh at least once a day. The only grandparent I knew was my paternal grandfather, remembered by most as a grumpy old man, and he probably was very grumpy for the good reason that he was confined to bed 24/7 following a stroke.

My grandfather’s house

My mind drifts back some sixty years ago, remembering when, as a troublesome child, I was sent to stay at his place when my parents needed time out. In my grandfather’s house also lived an uncle who had a severe limp as a result of childhood polio, and an aunt whose nervous affliction was never divulged to me. Her twisted hands and feet, and screwed facial features suggested that she was in constant pain. Whatever angst my behaviour had caused my parents must have been serious enough for them to think that I deserved to be exiled with these three elderly relatives in varying states of decrepitude.

Grandfather’s house at 6 Rue Edison, Rose-Hill, Mauritius

Grandfather’s house in Rose-Hill, with its large basalt steps leading into a ‘varangue vitrée’, filled with ferns and cane furniture, is etched in my memory.

So are the smells that greeted me upon entering. First was that of floor wax which had been laboriously applied by hand, then worked into the wood with the help of half a dried coconut husk. There was a special technique to shining the floorboards, which was to place one foot with your full weight on the coconut husk, and to move that foot with an energetic backwards and forwards rhythm, keeping your hands behind your back. A daily task for the maids, and one which I came to enjoy once I got the swing of it.

Along the shiny hallway we passed Uncle’s bedroom on the right, Auntie’s on the left, with its scent of 4711 Eau de Cologne, her favourite. Then into the dining room, from where a door on the left opened into Grandfather’s bedroom which smelled of ‘savon de Marseille’ and stale talcum powder. Depending on the time of day, delicious aromas would waft from the kitchen on the right. The dining room opened on to the back verandah whose overpowering stench of cat pee became associated with my retreats. I could close my eyes and know exactly where I was in that house.

A difficult and devout child

Spending time there was like being sent on a retreat, but I actually didn’t mind. Steeped in catholic guilt inflicted by Loretto convent nuns, I accepted my exile as a necessary means of redemption. Weekly confessions could obviously not cleanse me of my sins of telling lies, disobeying my parents, and being a glutton. My penalty was to recite one Lord’s prayer and ten Holy Mary’s, but I went much further, offering nightly prayers in exchange for world peace. We were in the midst of the Cold War and the daily news terrified me. I looked upon my retreat as a further measure to help prevent a nuclear attack which I believed to be imminent.

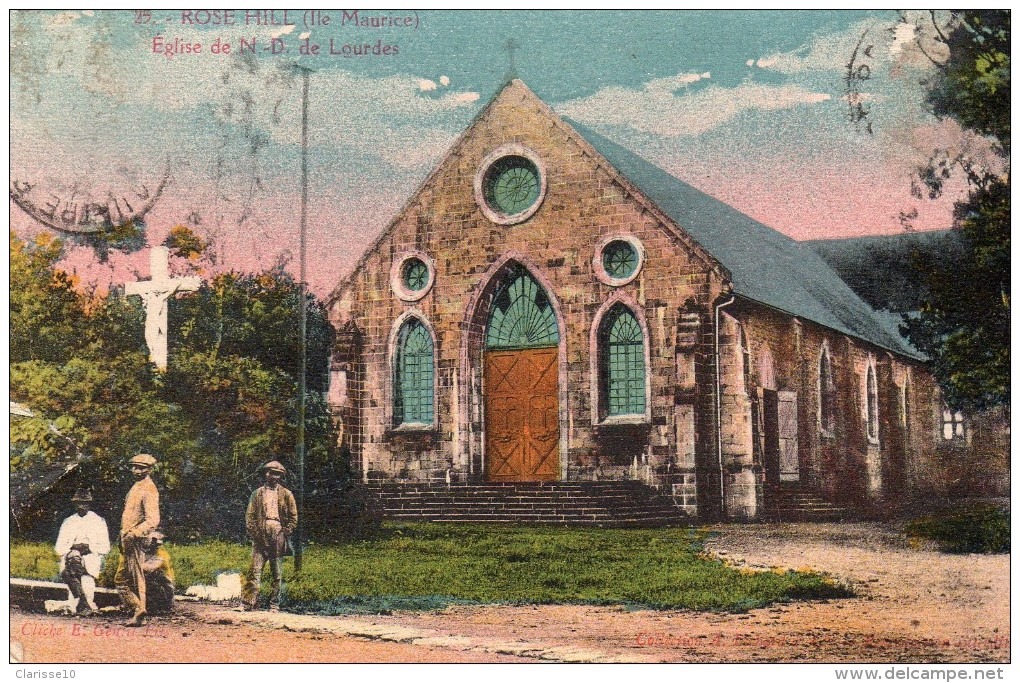

I remembered how I had embraced my aunt’s devoutness, rising with her daily at 4.30AM to walk a slow mile in darkness to Notre Dame de Lourdes church, which I remember as a stern grey edifice on Royal Road, Rose-Hill. I have found this very old photo in Histoires mauriciennes.

Notre Dame de Lourdes, Rose-Hill, Mauritius

Notre Dame de Lourdes, Rose-Hill, Mauritius

I remember how the thick stone walls enveloped us and a handful of other parishioners in a chilly silence. We entered through the vestibule, where we dipped our fingers in the stoup, and crossed ourselves as we genuflected before heading for a front pew where we heard mass celebrated in Latin. I recited every word and understood none. We breathed incense to purify our souls and took communion on an empty stomach. One hour later, as we exited via the side door, I felt the warmth of the sun on my face and felt closer to heaven. The aroma of freshly baked pastries drifted from Unic store patisserie across the road, but we turned left and trudged another slow mile back home.

Rose-Hill market

Despite my grandfather’s constant growling, I loved him, but I especially loved his soup, a thick vegetable broth full of small creamy yellow potatoes, sweet carrots, beans and other seasonal vegetables that Uncle would buy daily at the Rose-Hill market, and where I was privileged to be able to accompany him in his little grey Mini Minor, this icon of Britishness that did wonders in the colonies.

The market comprised a rambling construction of timber posts and corrugated iron roofs which harboured rows upon rows of locally grown fruit and vegetables picked daily and displayed in large baskets balanced on wooden crates. In summer, there were mounds of mangoes and small sweet yellow pineapples, bunches of lychees and longanes. Tomatoes, potatoes, carrots, onions, cabbages, beans, peas were piled high. There were also the ‘exotic’ vegetables such as bitter melons, occras, pipengailles (a type of gourd), and the various brèdes, leafy green vegetables such as watercress and brèdes songe (taro leaves) that grew wild alongside streams.

There were fresh herbs like thyme, parsley and coriander, garlic and ginger, all of which are the basic ingredients of just about every Mauritian dish. There were baskets of rice and pulses such as lentils, split peas, broad beans, lima beans, red kidney beans, and white beans; raw peanuts, boiled peanuts and shelled peanuts that had been roasted, salted and died pink; there were medicinal plants such as the digestive and soporific ayapana, as well as other fresh herbs that could help you lose or gain weight, fix your fatty liver, control your blood pressure, and relieve the discomfort of haemorrhoids. There were herbs for aphrodisiacs, but I am not sure if they were deemed to enhance your condition or temper your behaviour. If you wanted to pep up your energy, this is where you came, and an Indian stall holder would prescribe the herbs and dosages necessary to remedy your ailment. Everything was sold loose, wrapped up in newspaper, no plastic bags in those days.

Indian ladies in colourful saris squatted in every street corner behind glass cabinets filled with salted green mangoes, gateaux piment (chilli cakes), samoussas, and dholl puri, a Mauritian adaptation of Indian flatbread, made with flour and yellow split peas and eaten with a spicy tomato sauce or achard, an Indian vegetable pickle. (Dholl puris are claimed to be the national food of Mauritius, see recipe at https://www.sbs.com.au/food/recipes/dholl-puri)

Market shopping was over and done with by mid-morning, after which the long rest of the day dragged on for an eternity. Boredom looms large in my childhood memories.

Sharing long afternoons with Minou

Left to my own devices while my elderly relatives dozed the afternoon off, I roamed the garden in the company of a large ginger cat who, like most cats in Mauritius, was called Minou (females were called Minette).

In the front of the house was a small patch of lawn in the middle of which was a rain gauge that we were not allowed to touch until the level had been reported to Grandfather. God only knows what purpose this knowledge would have served him then, but I obeyed. From there we strolled along the poinsettia lined driveway leading to a rickety garage. Ripe mangoes plopped on its flat corrugated iron roof, where they were left to rot, releasing a sickly nauseating smell that attracted swarms of flies. Then on to the other side of the house which was dominated by a large pomegranate tree. I remember splitting open the fruit and carefully picking out the seeds, crunching them one by one. Minou closed his eyes as he licked the crimson juice that slowly trickled down my wrist, and it felt like partaking in a blood pact with a very special friend. Our final destination was the back of the house where we sought shelter from the heat of the day. Slumped by my side under clumps of banana trees, Minou would hear my stories, my songs, and my prayers for world peace.

I remembered how we nearly lost him, when we thought his infected wound was beyond healing. My father, who was an anaesthetist, was called to put an end to his misery, and he administered an injection that caused Minou to seemingly drop dead. His body was laid to rest in a back corner of the house and the men promptly forgot about him. Any feelings of discomfort they may have had for dispensing of the life of the mouse catcher was soothed by a few scotches over games of dominoes that lasted well into the night.

Sobbing into my pillow, I added Minou to my prayers, knowing how much lonelier my time in Rose-Hill would be without him. But miracles did happen then. Three days and three nights after being put to sleep, Minou rose and strolled into the house miaowing loudly for his food. None of us questioned the will of God, we simply rejoiced and christened him Lazarus.

A nuclear attack might yet have occurred, I had thought then, but my prayers to save Minou (he would always be Minou to me) had been answered. My exile had not been in vain after all.

A couple of hours and some sixty years later, the twins are waking …

5 Comments

Great to find you writing again. The girls must be asleep!

Hello Christiane

I had not visited my site for weeks, and have only come back to it after a hectic schedule with the girls. I would love to start posting again. At present you are probably still in Spain, recovering from waling the camino. I enjoyed following your progress as well as that of a close friend of mine who has just completed another epic journey. It is on my bucket list, but much else awaits.

How well I knew that house, the pencil drawings of Navy boats on the garage walls, the cats walking all over the furniture and kitchen ceiling beams, I too was left there to spend the day as Auntie was my Marraine.

I cannot remember the navy boats, Jean-François, I wonder who drew them? Tante J. was my marraine too and Tonton S. was my godfather, so it seems I had double reason to spend time there.

Thanks for the memories, Di.