Pandemic malaise

The water had seeped in ever so quietly through the tile grouting. I never thought that the big puddle outside the office, resulting from a broken downpipe, was finding its way inside the house. We had enjoyed the heavy rains that had finally broken the drought, making it more enjoyable to work in the garden with its new lease of life. Birds, bees, worms, were all busy once again. And me too.

Other than a compulsion to propagate, plant, prune, feed, and mulch, lock-down had triggered in me a frenzy of cleaning, sorting, and organising stuff. For whatever reason, I needed to make sure that my life and home were going to be in perfect order for when friends and family came to stay once travel restrictions eased. Or should I owe this flurry of activity to my subconscious awareness that I was amongst the vulnerable group with respect to Covid-19, hence the need to put my affairs in order. Just in case, je ne sais quoi.

Photos gone, but no so the memories

By the time I got to the large box under the desk, it had fused to the now very dry floor. The cardboard box had sponged up the water up to one third of its capacity, fusing its contents into one solid mass. Gone was my collection of old family photos, the only mementos of my mother and her family in the 1930-40’s in England, those of my family in Mauritius in the fifties and early sixties, as well as some of our early life in Australia soon after we emigrated in 1966. They had all coagulated into a thick sepia mass no part of which was worth saving. As I tried to peel individual photos from the block, they disintegrated into a powdery mess, leaving a barely distinguishable blur of images that I managed to identify only because I had so often pondered over them, trying in vain to reimagine my mother’s youth. What were her loves, dreams and hopes, of which she shared so little? I knew only that she harboured a secret deep in her heart of hearts.

Adstock and environs

My mother did, however, speak often of the beauty of the countryside where she grew up. She was born in Adstock, a tiny parish between Buckingham and Winslow in the Aylesbury Vale district of Buckinghamshire. Its population hovers around 350 and the only landmark of interest seems to be the parish church, St Cecilia, which dates back to the 12th century.

But she did speak fondly of the surrounding countryside, the brooks, the hills and dales across which she wandered endlessly; her eyes would light up as she described the bluebells, the daffodils and hyacinths that burst through the ground come spring, the cottage garden full of lavender which was used to make sachets that would rid their wardrobes of pests. She recalled the birdsongs that she could no longer enjoy in Mauritius and Australia (despite the claim that all bird songs originated in Australia!). She pined for the lyrical sounds of blackbirds, nightingales, robins, woodlarks, but none more so than that of the ‘wise thrush’ who ‘sings each song twice over, / Lest you should think he never could recapture/ The first fine careless rapture!’ (Robert Browning Home thoughts from abroad).

Thoughts of home in fact never left her. Neither did her copy of the Oxford Book of English Poetry, gifted to her by ‘a grateful patient’ in November 1937.

Thoughts of the English countryside were the only ones that would brighten her final moments almost a century later in Australia.

Oh! to be in England

All those years later, as I read Melissa Harrison’s All among the barley, how I wished that this book had been published before she died. How she would have enjoyed reading this description of the English countryside:

Above me, lost in foliage, a robin was singing quietly to itself under its breath; not in full-throated song, but as though practising, working out the notes as a man might hum a tune he aims to learn. In a few months, I reflected, it would be the only bird singing in the valley; the throstle would call out a few phrases in midwinter, but for the most part there’d be little music between harvest-time and spring. But spring would come, and the ground would warm again, as it always did, and all the summer birds, including Edmund, would one by one return to make and build their nest. The bluebells would come out in Hulver Wood and our bees would wake and begin to forage; the grass would grow tall in the hay meadows and be mown, the peas would blossom once more and smell sweet. And the cornfields would be green, then grow tall and turn golden; and so would pass the next year, and the next.’ (p.153)

All among the barley is set in 1933. Mum would have been seventeen, just a little older than the protagonist, Edith June Mather, who was born not long after the end of the Great War.

But back to the photos.

Family photos

None of the photos was redeemable, but I needed no effort to commit them to memory before throwing them out, one by one.

My favourite was the one of my mother with her mother. They are standing in front of a low white fence in an open field. Grandmother is very thin, she is probably already consumed by the leukemia that would end her life a couple of years before my birth. They look straight at each other, smiling. They look close, and yet I believe Mum did not attend her mother’s funeral. I never found out why, she would never tell me why, another one of her secrets. So much of her youth remains a mystery.

They must both by then have overcome the grief of losing an adored husband and father, who was gassed in WWI and died of his injuries. Mum spoke of her father with such pride, recounting his passion for gardening and how he had grafted a new variety of melon. She also spoke highly of her mother, lauding her culinary skills, remembering how her nimble fingers worked flour and butter on their wooden kitchen table to make perfect pastry in minutes. Her apple pies were legendary, made with the famous Cox’s Orange Pippin, a cultivar first grown in 1830 in Buckinghamshire by the retired brewer and horticulturalist, Richard Cox. The Cox, as it was commonly known, found no match in Australia, but my mother ‘s apple pies were nevertheless amongst the best I have ever tasted. She had no doubt inherited her mother’s talent for making pastry.

There are some photos of the family – Grandmother, Mum and her twin brother, and two older brothers. The boys, or rather the men, as they would have been in their twenties, are in suits. The three side by side stand behind the women. Grandmother lies on the grass, patting her dog, a white labrador who looks like it wants to play. Mum is by her side, looking beautiful. In the background an open field with clumps of wildflowers stretches as far as the eye can see.

These photos must have been taken before WWII, when it was still possible for Mum to take a break to go visit her family. She had left home soon after finishing secondary school at the Royal Latin School that she attended after winning a scholarship. She liked to tell us how she walked the six miles from Adstock to school and six miles back, but this would have been a singe for an overactive teenager engrossed in Nature and all the plants and creatures therein. For us pampered children growing up in the torrid climate of Mauritius, these daily walks would have been impossible feats.

Nursing in London

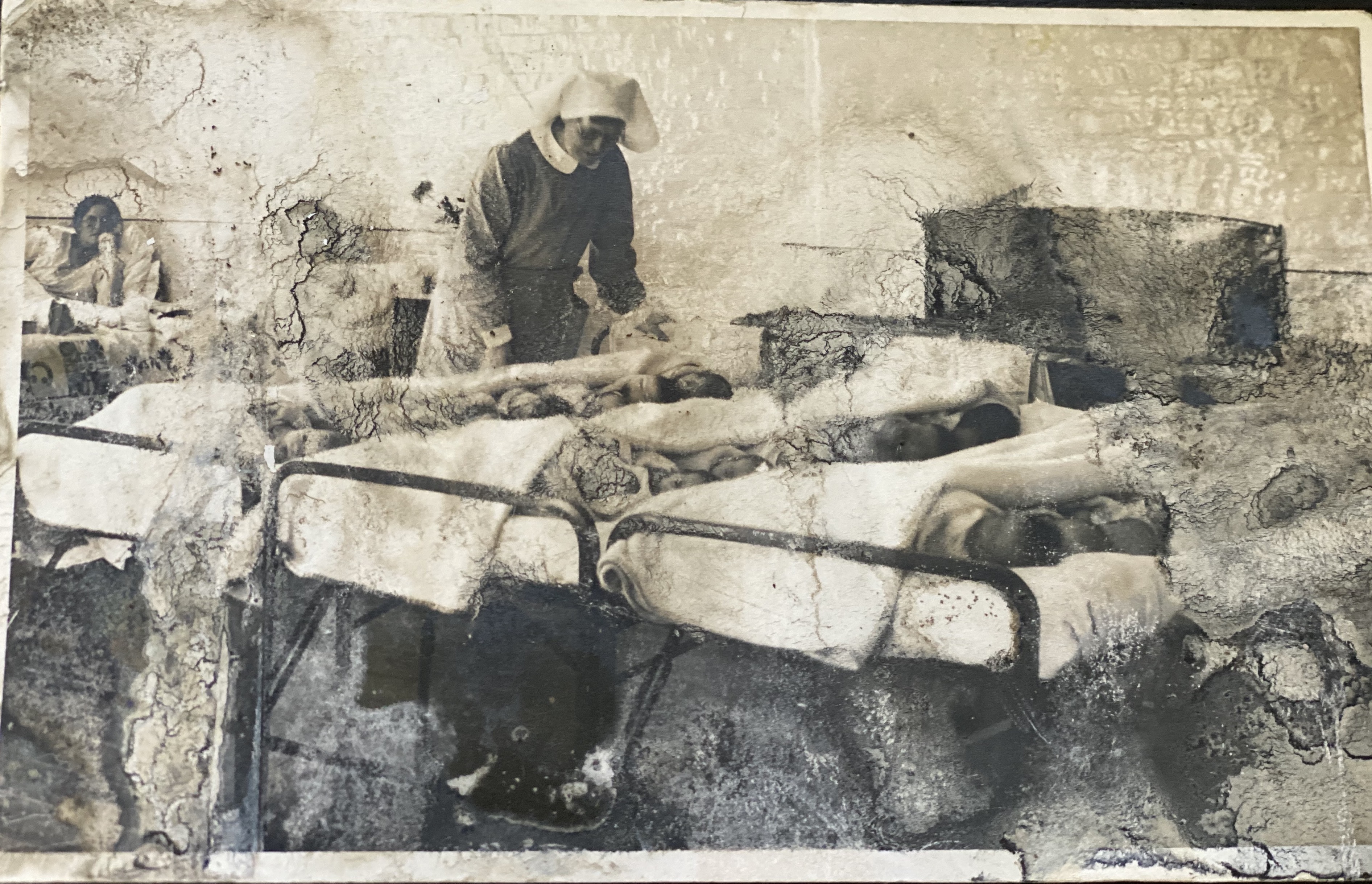

The next photo is one of a hospital ward, in one of London’s hospitals where my mother worked during WWII. In the background are two single beds with new mums sitting up. One is holding her baby. A nurse is standing next to one of three other single beds side by side covered with babies lying sideways, tightly packed like so many sardines. I can count 6-7 babies to each bed. No such thing as individual cots then!

There is another photo of new mums in single beds, with nurses attending to them. One of the nurses looks like Mum. She is laughing, obviously enjoying what she is doing. Had she already met my father? He would by then have won the prestigious UK Scholarship that would allow him to study in England. He chose Medicine, and their paths were set to cross.

By the time her future husband arrived as a medical student, she was a qualified midwife who had assumed responsibility both for the management of the nursery and the training the medical students. Photos of the nursery with its rows upon rows of tightly swathed newborns suggest that it was run with military precision. There was no flinging of arms by these babies who would be fed, winded and wrapped up like so many cocoons to simulate the womb environment. The baby boom had started and she would later contribute with four children of her own.

A game of tennis

They had met in a London hospital. He was one of her students, four years younger than her, brilliant, with a perfect mastery of the English language though it was not his mother tongue. A painfully shy, slightly built young man whose dark brown eyes and shot of black hair would have been nondescript in Mauritius, but would come across as rather exotic in this new environment. She was tall, strong, athletic, an excellent teacher and confident public speaker. I had often asked Mum to talk about their romance, begging for details of her emotional journey, but Matter-of-fact Mum only mentioned being invited to a game of tennis when she thrashed him. The romance pretty much took off from there, she would say.

There is a final picture from that period, one of my parents in France, possibly during their honeymoon, soon after they married on August 26 1946. It is by a roadside, in the country somewhere in France. Mum is lying on her stomach, my father holds a bottle of wine and a baguette. They look very happy and carefree, perhaps dreaming of their next adventure.

My father was by then a qualified doctor, but there was no prospect of work in London, and in any case, the terms of his scholarship may have stipulated that he return to practice in Mauritius. And so it was that they set sail from Liverpool soon after the birth of my older brother in June 1947.

Mum recalled how, prior to leaving, she had to sell her iron and ironing board to make ends meet. But the war had ended and their future in the idyllic tropical island of Mauritius promised the fulfilment of their dreams.

1 Comment

Beautifully written Di. Thank you! Looking forward to the next essay.